Apologies, but no results were found for the requested archive. Perhaps searching will help find a related post.

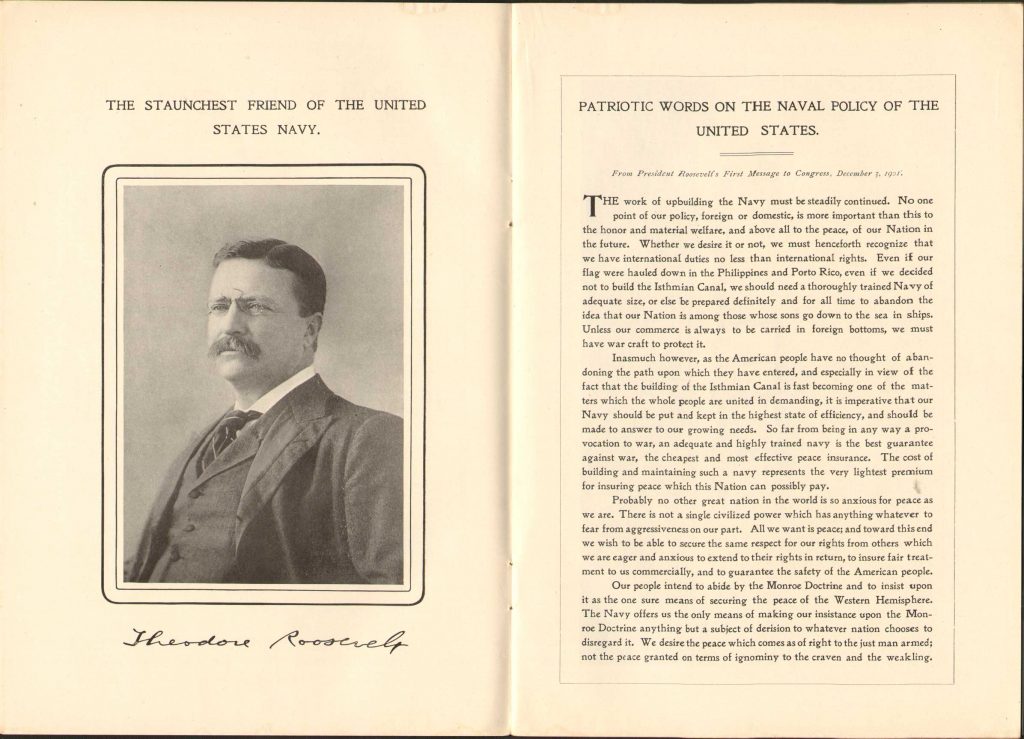

Before becoming president, Theodore Roosevelt had been Assistant Secretary of the Navy. In a speech before Congress on December 3, 1901, Theodore Roosevelt outlined the importance of a strong Navy. "No one point of our policy, foreign or domestic, is more important than this to the honor and material welfare, and above all to the peace, of our Nation in the future."

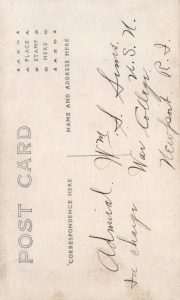

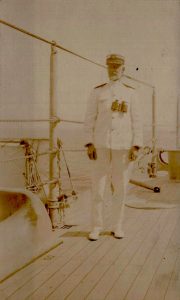

commanders and captains

- Commander-in-Chief , Theodore Roosevelt

- CIC, Atlantic Fleet, Robley D. Evans (first leg)

- CIC, Atlantic Fleet, Charles M. Thomas (interim)

- CIC, Atlantic Fleet, Charles S. Sperry (second leg)

- Commanding, Second Division, Richard Wainwright

- Commanding, Third Division, Seaton Schroeder

- Commanding Fourth Division, William Emory, USS Kansas

- Captains of the Fleet

Theodore Roosevelt was one of the most knowledgeable, if not the most knowledgeable, president on the use of naval power. His education started when he was just a boy hearing tales of his two uncles that had served as naval officers in the Confederate Navy. He loved military history and, as a young student at Harvard, was upset by the fact that one only authoritative book written about the naval battles of the War of 1812 were written by British authors. Roosevelt, while still a student, set to work to learn everything he could about ships and the battles, writing a technically accurate account. His book, "The Naval War of 1812" was published while he was in study at Columbia Law School. It was immediately recognized as an excellent work of historic accuracy. The New York Times review: "A young politician like Mr. Roosevelt has a wider scope for his mind than wire-pulling and has made at least one period of American history the object of serious study." Further stating, "The volume is an excellent one in every respect, and shows in so young an author the best promise for a good historian -fearlessness of statement, caution, endeavor to be impartial, and a brisk and interesting way of telling events."

At 22 years old he had established his credentials as an expert on Naval affairs. The Naval War of 1812 sold out in it's first and second printings and was hailed by naval experts in the United States and Britain as an authoritative work and adopted as a textbook at several colleges. In 1886 the U.S. Navy put a copy on every warship. It is still regarded as the definitive work on the subject.

On May 10th and 11th 1890, Theodore Roosevelt read a newly published book that would change our Navy and the view of our relations with the world forever. It was Alfred Thayer Mahan's "The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783." Roosevelt finished it as a weekend read and never forgot what he learned from the book. After reading the book Roosevelt wrote a note to Mahan, "During the last two days I have spent half my time, busy as I am, in reading your book. That I found it interesting is shown by the fact that having taken it up, I have gone straight through and finished it . . . It is a very good book - admirable; I am greatly in error if it does not become a naval classic." (It did become a naval classic and is required reading still at the Naval Academy)

Mahan was an active duty naval officer and served as President of the newly established Naval War College. In his desires to stay at the War College and continue writing he wrote Roosevelt for support. l Roosevelt was still a young politician and could do nothing t prevent Mahan's transfer back to sea.

in 1896 Roosevelt worked to get William McKinley elected president while he was a young New York politician. He was rewarded with an appointment as Assistant Secretary of the Navy. Within weeks he was involved with all aspects of running the Navy. Mahan, now retired, wrote to him shortly after taking office, "You will, I hope, allow me at times to write to you on service matters, without thinking that I am doing more than throwing out ideas for consideration."

It was in these discussions that the annexing of Hawaii was discussed as necessary to prevent the Japanese from taking control. Roosevelt continued to exchange letters till the start of the War against Spain in 1898. He was integral in the appointment of key people to positions of importance, such as Dewey, Evans, and Sampson, the key leaders of the fleet battles of the war. But soon he felt he had done what he could for the Navy and that Secretary Long could handle things if he left. He resigned his position to for a regiment in the Army, the Rough Riders.

Secretary Long noted in his journal, "My Assistant Secretary, Roosevelt, has determined upon resigning in order to go into the army and take part in the war. He has been of great use; a man of unbounded energy and force, and thoroughly honest, which is the main thing. He has lost his head in this unutterable folly of deserting the post where he is of most service and running off to ride a horse and, probably, brush mosquitoes from his neck on the Florida sands. His heart is right, and he means well, but it is one of those cases of aberration-desertion-vain glory; of which he is utterly unaware. He thinks he is following his highest ideal, whereas, in fact, as without exception, he is acting like a fool. And yet, how absurd all this will sound if, by some turn of fortune, he should accomplish some great thing and strike a very high mark."

His return from Cuba following the success of his "Rough Riders" led to his election as Governor of New York in 1898. It followed that he became his party's nomination for Vice-President two years later and in September 1901 became President upon the death of William McKinley.

One of his first actions regarding the Navy was to set about improving their gunnery skills. Working with William Sims, a young naval officer as the Inspector of Target Practice. By 1903 they had improved the fleet's performance to the best in the world. In 1902 Roosevelt supported the first two Connecticut class battleships and later in his administration 4 more. As the Navy grew to the goal of President Roosevelt, he watched and studied the growth of other navies and the war between Russia and Japan. Though this whole period he kept his two close advisors, Mahan and Sims.

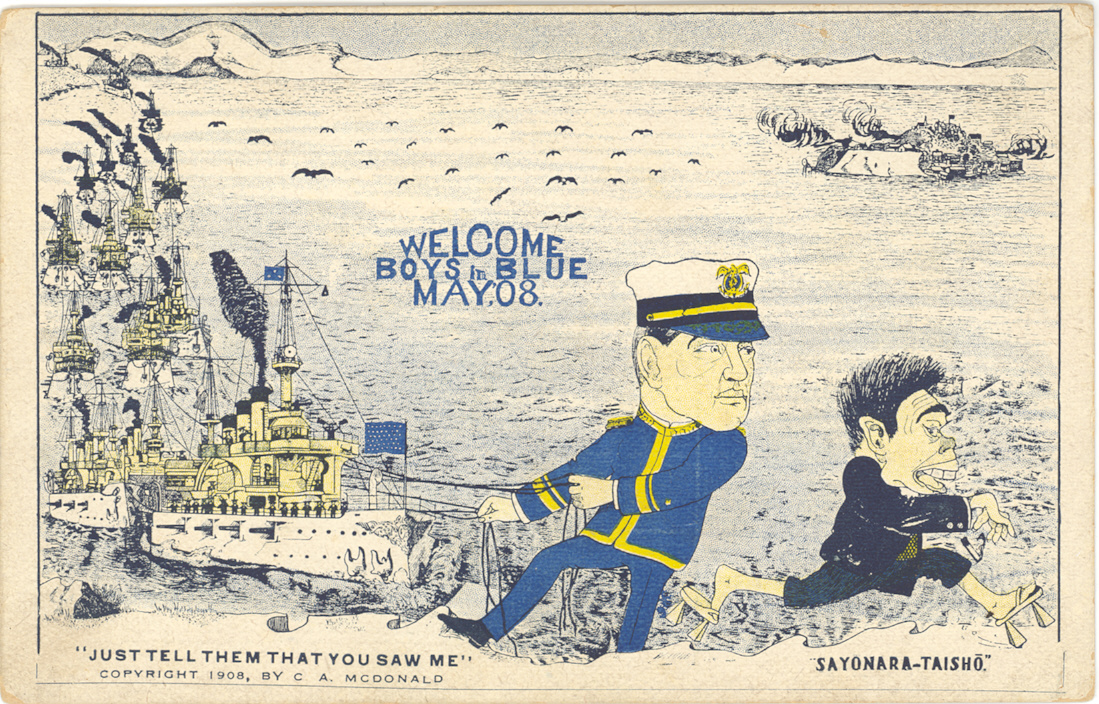

It was Mahan who continually sounded the alarm regarding Japanese expansionism in the Pacific to Roosevelt, who, with each passing year, he started to take more seriously. Immigration of Japanese to the west coast exceeded limits that had been established and the fleet on the west coast, as well as the naval facilities were substandard. Sometime around June 1907, Roosevelt decided to move the fleet from the east to the west coast. It was clear he felt our fleet in the Pacific could not defend the possessions of the Philippines and Hawaii and the situation in California including riots over allowing Japanese children into public schools and limiting immigration required action.

In a sense, Roosevelt was negotiating with the Japanese over these issues but did not feel he was dealing from a position of strength. Two years after leaving office he wrote: "I had been doing my best to be polite to the Japanese and had finally become uncomfortably conscious of a very slight undertone of veiled truculence in their communications in connection with things that happened on the Pacific Slope; and I finally made up my mind that they thought I was afraid of them . . . It was time for a show down . . . I had great confidence in the fleet."

By this time the Japanese fleet had proven itself as a formidable foe, they had destroyed the entire Russian Fleet. In the Battle of Tsushima Straits, May 14,15, 1905, they sunk or put out of commission 28 of the 32 combatants of the Russian Navy in less than 24-hours. The Russians lost 4,380 killed and 5,917 captured, including two admirals, with a further 1,862 interned. They lost 11 battleships, 4 cruisers, and six destroyers. It was a humiliating defeat for the Russian Navy. The whole world took note.

It seems clear that at the time of the fleet's departure there was not intent for war with Japan, but it was also clear Roosevelt wanted to show that America had every intent to protect our interests. Impressing the Japanese was an interest and possibly a key reason to send the fleet around the world instead of stopping in California.

To an American diplomat Roosevelt wrote, "I am exceedingly anxious to impress upon the Japanese that I have nothing but the friendliest possible intentions toward them, but I am none the less anxious that they should realize that I am not afraid of them and that the United States will no more submit to bullying than it will bully."

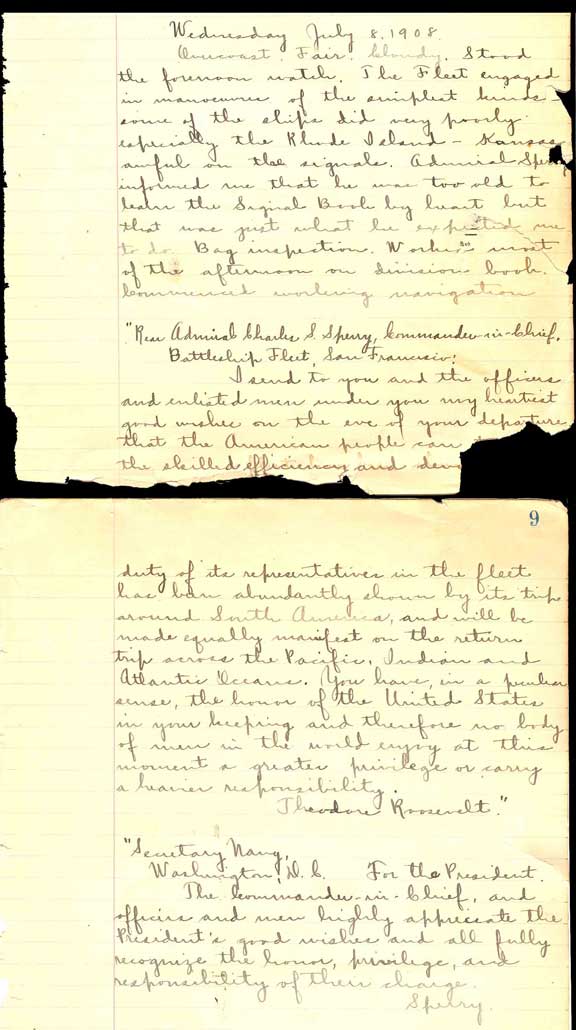

At left is a page from the journal of Midshipman Loftquist who sailed with the fleet onboard the USS Connecticut. His entry for July 8, 1908 describes his duties on the bridge and transcribe copy of a letter from President Roosevelt sending the fleet on it's journey around the world.

He next transcribed the response written by Rear Admiral Sperry. The message was read to all crewmembers, and all ships of the fleet as they prepared to depart San Francisco on their historic journey:

Rear Admiral Charles S. Sperry Commander-in-Chief Battleship Fleet, San Francisco:

I send to you and the officers and enlisted men under you my heartiest good wishes on the eve of your departure that the American people can trust that the skilled efficiency and devotion to duty of its representatives in the fleet has been abundantly shown by its trip around South America, and will be made equally manifest on the return trip across the Pacific, Indian and Atlantic Oceans. You have in a particular sense, the honor of the United States in your keeping and therefore no body of men in the world enjoy at this moment a greater privilege or carry a heavier responsibility.

Theodore Roosevelt Secretary Navy Washington D.C.

For the President,

The Commander-in-Chief, and officers and men highly appreciate the President's good wishes and all fully recognize the honor, privilege, and responsibility of their charge.

Sperry